Italian Fashion Industry - Cycles of Development

Though some could argue otherwise, according to the experts in Italy, there are 4 primary phases or cycles of Italian fashion industry development.

- 1950s-60s: Industrial production systems are developed after WW2

- 1960s-70s: Economic and social change emerges, apparel system reacts

- 1980s: Democratization of fashion and surge of "Made in Italy" around the world

- 1990s: Brand concentration, financing revisions and mergers & acquisitions

The 1st Cycle: 1950s-60s

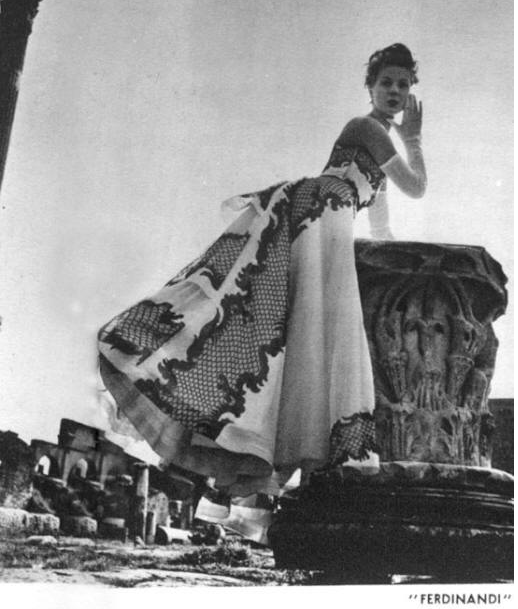

Prior to industrial developments in Italy, which occurred only after WW2, 90% of Italians were rurally employed. The elite acquired their luxury products from France, and Italian goods were considered "poor". Most higher fashion was reserved for men, as women did not have as many black tie events to dress for.

At the time, the fashion industry in Italy was largely non-existent. With the high-end consumers buying their fashions from Paris, or having copies made by local tailors, some industrialists noticed a gap in the market supply, which called for functional, durable, high quality garments. To begin to meet this demand, Italian company Gruppo Finaziario Tessile (GFT) took the first initiative to measure a wide sample of the Italian population to create national sizing system.

Italian Apparel Finds a Niche

In 1951, an Italian importer for American goods, named Gian Battista Giorgini, realized the the US market was also ready for something new and different from that offered by France. They had mass-produced garments, the elite could buy haute couture from Paris, and yet there was nothing in between. Giorgini used his US contacts for market research and development, and began to organize Italian designers, whom he encouraged to abandon their French knock-offs and pursue an affordable Italian style. With new production technologies from the States being imported into Italy as part of the recovery plan, and a large skilled workforce of women to operate the machinery, GFT and other Italian manufacturing firms such as Marzotto and Lebole developed the production end of the industry. As many of top producers had a background in men's tailoring, there was still a strong industrial concentration in menswear, but the mass-production capabilities in the States would find their way into Italian womenswear production soon enough.

In 1951, an Italian importer for American goods, named Gian Battista Giorgini, realized the the US market was also ready for something new and different from that offered by France. They had mass-produced garments, the elite could buy haute couture from Paris, and yet there was nothing in between. Giorgini used his US contacts for market research and development, and began to organize Italian designers, whom he encouraged to abandon their French knock-offs and pursue an affordable Italian style. With new production technologies from the States being imported into Italy as part of the recovery plan, and a large skilled workforce of women to operate the machinery, GFT and other Italian manufacturing firms such as Marzotto and Lebole developed the production end of the industry. As many of top producers had a background in men's tailoring, there was still a strong industrial concentration in menswear, but the mass-production capabilities in the States would find their way into Italian womenswear production soon enough.

You could summarize that the beginnings of the Italian Fashion Industry were characterized by:

- Large manufacturing facilities

- Economies of scale (primarily the US market)

- Strong specialization

The 2nd Cycle: 1960s-70s

In most cultures, up until this point, children and adolescents had dressed as their parents dressed. In the States and the UK, pop culture shifted in the wake of the Baby Boom as young people struggled to develop a new identity and used fashion as a means to demonstrate their separation from the values of their parents' generation. (England was becoming a hub for the new youth culture, inspiring fashion and trends around the world, in addition to American hippies.) Women had entered the workforce in increasing number, and no longer wanted to dress as housewives. Further, as there were fewer and fewer occasions for dressing up, people began to seek more informal clothing. Trends had begun to be driven by market needs, as opposed to the stylistic direction set in Paris.

In most cultures, up until this point, children and adolescents had dressed as their parents dressed. In the States and the UK, pop culture shifted in the wake of the Baby Boom as young people struggled to develop a new identity and used fashion as a means to demonstrate their separation from the values of their parents' generation. (England was becoming a hub for the new youth culture, inspiring fashion and trends around the world, in addition to American hippies.) Women had entered the workforce in increasing number, and no longer wanted to dress as housewives. Further, as there were fewer and fewer occasions for dressing up, people began to seek more informal clothing. Trends had begun to be driven by market needs, as opposed to the stylistic direction set in Paris.

Big Business Gets Smaller

At the same time, there were many social and union conflicts that helped create increased labor costs in developed countries, resulting in a surge of apparel imports from developing countries. The combination of these elements together with the oil crisis of 1974 and the Italian economic crisis of 1975 caused the big manufacturers to lose their hold on the mass market. There was no longer a one-size-fits-all model for fashion (and that was only the beginning, as we now know!).

At the same time, there were many social and union conflicts that helped create increased labor costs in developed countries, resulting in a surge of apparel imports from developing countries. The combination of these elements together with the oil crisis of 1974 and the Italian economic crisis of 1975 caused the big manufacturers to lose their hold on the mass market. There was no longer a one-size-fits-all model for fashion (and that was only the beginning, as we now know!).

As the big manufacturers in the States and elsewhere had maintained large scale standardized production even after consumer demand had decreased and diversified, the labor costs in Italy were falling and new small/medium-sized production companies were forming. Manufacturers began to outsource production in Italy, and even France began to rely heavily on the cheap yet skilled Italian labor pool for their pret-á-porter lines.

Designers Respond to a Changed Environment

A new generation of designers emerged in Italy, capable of working with industry partners to produce collections that were fashionable and more affordable than their French counterparts. (Consider Armani & Cerruti, Versace & Genny, or Soprani/MaxMara.) These designers had relationships with market-savvy business leaders, who ensured that the Italian form of fashion would meet the demand of developed markets. The Italian Fashion Week cycle, following on the heels of Paris, became increasingly popular to buyers and press who saw the potential of Italian fashion's middle ground between haute couture (France) and mass fashion (the US).

A new generation of designers emerged in Italy, capable of working with industry partners to produce collections that were fashionable and more affordable than their French counterparts. (Consider Armani & Cerruti, Versace & Genny, or Soprani/MaxMara.) These designers had relationships with market-savvy business leaders, who ensured that the Italian form of fashion would meet the demand of developed markets. The Italian Fashion Week cycle, following on the heels of Paris, became increasingly popular to buyers and press who saw the potential of Italian fashion's middle ground between haute couture (France) and mass fashion (the US).

In summary, this cycle of development in the industry of Italian fashion can be characterized by:

- New consumer values and lifestyles (youth, rebellion, rock, women in business, etc)

- Market segmentation (no longer one-size-fits-all)

- Increased demand for informal wear

- The decrease of influence from Paris and haute couture

- The increase of influence from London and the youth culture

The 3rd Cycle: 1980s

This was the decade where the world found Italy.

This was the decade where the world found Italy.

By the 1980s, Italy had little competition from other developed countries for quality textile production. However, developed markets were building a habit a rampant consumerism, with a renewed interest in fashion. The Italian style had gradually been gaining consensus, especially in the States, which had become the largest consumer market. Meanwhile, Italian industry was looking for new formulas to stay (or get) on top of the fashion game.

Total Look, Branding & Hollywood

A new type of relationship began to form between industry and the designers, which was more a partnership that a contractual business relationship. With the craze for "Total Look" taking the fashion scene by storm, designers began to throw their labels onto every conceivable product in their quest for notoriety and brand building.

Internationalization, mass media and the help of Hollywood brought Italian industry onto the main markets. For example, Armani exclusively clothed actor Richard Gere for his role in American Gigalo, bringing the brand notoriety throughout the States and abroad. You can see an early example of product placement with Armani's menswear collection in the closet scene of American Gigalo, in the clip below:

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bzh1iqt7Ij8]

Love for Licensing

Licensing agreements had become the method of choice for labels to expand their designer names into new product categories (including second and third lines, kids wear, athletic wear, homewear, eyewear, fragrances, etc.). The cooperation between industrial companies and designers, mainly based on these licensing agreements, was the key success factor to growth for the Italian fashion industry.

Fashion companies moved from product-specialization to develop multi-product capabilities through their licensees. In addition to manufacturing, licensees were used to handle distribution and retail activities for the licensor brands, while the brands in turn provided the design concept, the brand name and image.

Throughout the 80s, much of the Italian fashion system depended on licensing agreements for growth and for specialized production (after all, what does a ready-to-wear designer know about producing furniture or fragrances if he can't rely on experience professionals to help him?). However, as the brands amassed capital, and learned from their licensees about best (and worst) practices, it became clear that licensing could be equally beneficial and detrimental.

Brands like Gucci were widely diluted through numerous licensees, all whom had a different idea of what the brand represented and how their designs should appear and retail. On the verge of bankruptcy, they needed to build capital and buy back their licenses, in order to impose a universal brand strategy throughout their comapnies.

Within the decade, four different groups of players on the Italian fashion scene had clearly emerged. They were:

- Industrial companies (GFT, Marzotto, Miroglio)

- Small to medium-sized industrial companies with product orientation (Max Mara, Zegna, Genny, Aeffe, Ittierre)

- Designer/entrepreneurs who both design and produce (Missoni, Mila Shon, Mario Valentino)

- Pure designers who take designs to production firms (Versace, Armani, Ferré, Moschino, Krizia)

By the end of the 1980s, Italian designers had entered into a new system of growth:

- Most remained family industries (Missoni, Prada, Versace, etc)

- Designers maintained direct control over their "first lines" (the highest line in their brand's "food chain" - typically ready-to-wear)

- Brands developed second lines and brand extension, typically under general artistic direction of the original designer and through licensing agreements

- Brands developed direct control of distribution, taken back from licensees

- Focus was kept on retail, to create a unified harmony across a branded retail outlets

You could therefore conclude that the Italian model for the fashion industry, at this point, consisted of designers sketching models for the primary line, with manufacturing and additional product development farmed out to licensees, with the finished products then brought back under internal control for distribution and sales. Just ten years prior, licensees had handled everything but the initial design, brand name and image direction for the Italian brands.

Unlike France, Italy typically relied on lower-end textiles - not fragrances and accessories - to make the big money.

The 4th Cycle: 1990s

Towards the end of the 20th Century, the fashion system was undergoing many changes. The fashion system had become increasingly global in supply and demand, affecting Italian, French and American firms together.

Towards the end of the 20th Century, the fashion system was undergoing many changes. The fashion system had become increasingly global in supply and demand, affecting Italian, French and American firms together.

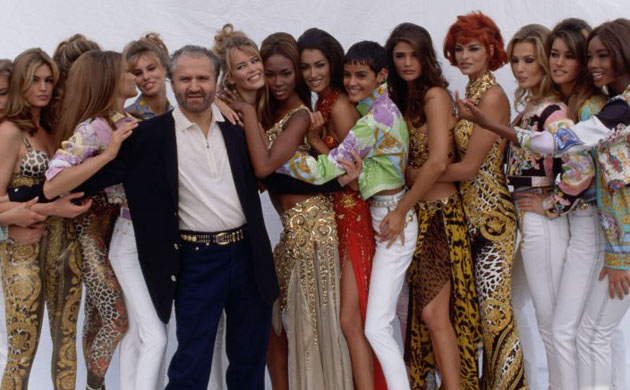

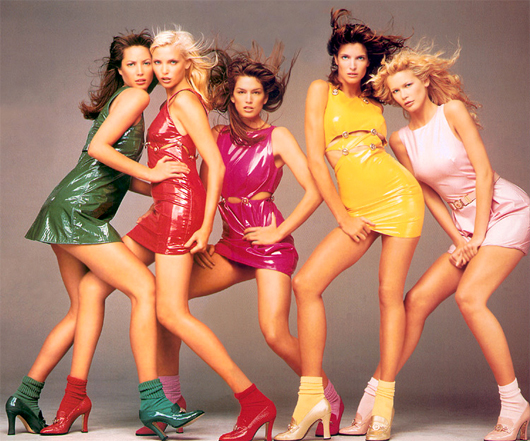

New players were entering the field; for example, the luxury conglomerates. New market segments were being created as well, including the bridge segment, which spoke to a market beneath ready-to-wear but above mass fashion. Entry barriers into the industry had become increasingly higher, with great investments required in marketing (fashion show and advertising extravaganzas, parties, supermodels, etc) and retail. Retail itself was undergoing change through the introduction of the lifestyle concept, pioneered by American designer Ralph Lauren.

New players were entering the field; for example, the luxury conglomerates. New market segments were being created as well, including the bridge segment, which spoke to a market beneath ready-to-wear but above mass fashion. Entry barriers into the industry had become increasingly higher, with great investments required in marketing (fashion show and advertising extravaganzas, parties, supermodels, etc) and retail. Retail itself was undergoing change through the introduction of the lifestyle concept, pioneered by American designer Ralph Lauren.

Fronting the Tab

In order to meet the new financing needs of the fashion system, many companies opened on the stock exchange. With this move came a market rush by the luxury conglomerates to acquire and reposition the Italian brands with marketable heritage. Much like the French houses before them, Italian brands were gradually having to transfer creative direction from the original designers onto new creatives.

As for the four groups of players on the Italian fashion scene, the 90s saw the following changes:

- Industrial companies: begin to acquire brands - typically from past licensors, launch their own brands based on their acquired capabilities, or develop retail strategies (Aeffe/Moschino, GFT/Valentino, Exté, Max Mara, Zegna)

- Designer/entrepreneurs: control production and distribution processes with the purchase of production facilities, utilize very few licenses (Versace, Dolce & Gabbana, Armani)

- Multibrand Groups: conglomerates acquire brands and designer companies (LVMH, Gucci Group, Prada)

- Pure designers: sell their companies to industrial or multibrand groups (Jil Sander, Valentino)

In "Short"

The Italian fashion industry really took off after WW2 with the help of technologies provided as part of the Recovery Plan, the entrepreneurship of business and manufacturing leaders who saw an opportunity, a newly-urbanized population of skilled textile workers, and a burgeoning demand for quality apparel and ready-to-wear.

The first phase of industrial fashion in Italy was made by a few concentrated, large-scale production facilities. As the economy turned south and many new market segments emerged, big business lacked the flexibility to diversify their business model, and small to medium-sized manufacturing companies took the lead.

Designers and their business partners (typically family) recognized the changing market as an opportunity, and developed partnerships with manufacturers who had once contracted work to them. Under this model, the designer became responsible only for the initial designs of his collection, while his business partners managed the brand and image, and licensees took care of the rest - from manufacturing through distribution and retail.

By the end of the 1980s, many brands had gained the capital and the knowledge base to buy back their licenses in specific product categories, as well as their distribution and retail systems. Some were able to purchase their own manufacturing facilities. The typical model now had the design company controlling the initial designs of the highest line and whatever licenses they had brought in-house, as well as their distribution and retail. Manufacturing was still typically licensed out.

During the final years of the 20th Century, the costs of running a fashion business had exploded with a need for mass marketing. Many companies went on the stock exchange to build capital investment. While some brands took control back from their licensees, others were acquired by luxury conglomerates. Some manufacturing leaders developed their own lines or acquired brands they had once licensed production rights from.