The power of social media is strong, and infographics are cool!

Read MoreReturn to "Luxury"

Luxury business leaders wise up and show signs of abandoning their mass-market strategies for a return to exclusivity and craft.

*Thumbnail credit, Tom Palumbo

Throughout the past few years, many luxury companies have followed the model of growth that includes frantic brand-buying sprees and diversification into complementary categories such as interior design and technology.

Based on the conversation among industry leaders that just closed in Monte Carlo at the Financial Times’ Business of Luxury Summit, that very trend is what will be avoided in the future, as luxury companies seek to preserve an image of quality in the eye of the consumer.

The Honeymoon is Over

During the boom years, many luxury companies ventured into secondary product and service endeavors spanning the range from cell phones to hotels, under the strategic principles that 1) these outshoots serve to further their brand image, 2) their reputation of quality could transcend from the product category they had built a name upon, and 3) that "everyone else was doing it" - they didn't want to be left out of the game.

Pushing the Brand Image

The idea that these complementary product categories could further the brand image began from the right perspective. After all, what better way to promote a fashion label's home collection than to furnish an entire hotel under the brand name? When coupled with the managerial expertise of EMAAR Hotels & Resorts, the Armani brand has done just that. However, the brand image of Armani was established in sartorial minimalism and modernity, and while that can be reflected in some ways through the environmental design of a hotel, to convey the brand experience through hospitality is another matter. With tourism lagging in the economic crisis, it is doubtful that Mr. Armani wants the concept of minimalism conveyed through empty hotels.

The real problem emerges when the brand image is exposed to elements outside of the company's core capabilities. Just as in licensing out fashion products for manufacture or sales to external parties, final control over the product and customer experience is lost. This poses a significant risk.

Transcending Quality

While the concept of co-branding is a nice way to give more consumers access to a brand they love, the benefits are often shortsighted. While the Total-Look trend died in developed markets in the 80s, co-branding projects served as a way to reignite the flame. Fashion companies went beyond the traditional accessories categories typically reserved for leather goods (shoes, bags, belts, etc) and began to venture into tech projects. Although this allowed several die-hard brand enthusiasts to more adequately encompass their life in a brand of choice, it also allowed some brand outsiders to have a "piece of the brand image" without the purchase of more traditional items.

I have several points on this: for the fashion-cell phone explosion, brands from Prada to Dolce & Gabbana and Armani have played the game, coupling brand imaging in aesthetics with the technological capabilities of LG, Motorola or Samsung, respectively. However, the development process for the Prada cell phone was tedious and expansive, and Prada had to sacrifice some brand imaging points while LG had to sacrifice some cutting-edge technologies to bring the project to fruition. An equal compromise in aesthetic and technological appeal serves neither the fashion brand nor the technology company. The expertise of neither brand could be fully conveyed in the project, driving the perception of quality down. This is what happens when you venture too far from your core capabilities, without enough understanding of the new category.

On the other hand, Hermes worked on a limited-edition co-branding project with Bugatti to create the Bugatti Veyron Fbg par Hermes. While Bugatti pumped this high-performance dream car full of the best automotive technology on offer, Hermes stuck to their core capabilities in leather goods and sartorial excellence to outfit the vehicle in the finest interior upholstery and complementary accessories. The resulting product is a $1.5 million car that definitely will not be driven by every brand enthusiast, but it certainly represented the best of both brands! Furthermore, the project achieved greater market exposure for Hermes and Bugatti through a lot of positive press coverage in both the luxury, fashion, automotive and leisure categories.

Playing the Game

For years, the idea that luxury was an easy business to make money from prevailed. Companies entered the sector and shortened product cycles, product categories offered, store locations, and so on in an effort to milk the market for all it was worth. According to Bernard Arnault, “Some investors pushed by the frenzy of doing something were going to invest in almost everything. As luxury was perceived as an industry where you can make money easily, they were pushed to buy brands without knowing how to make them work.”

As consumers were hungry for "more, more, more," the luxury companies were all too happy to provide it, with little consideration for consequences beyond the immediate bottom line. Referring back to brand diversification, CEO and founder of Tod's Spa Diego Della Valle noted, “Several times I had to fight for our vision against external pressures, which were demanding we did perfumes, or mobile phones. My answer was that it wasn’t our competency. If I want a mobile phone, I want to buy it from Nokia.”

With market pressures mounting, brands began to churn out an ever-increasing supply of product collections. The highest brands of luxury in fashion found themselves competing on the same playing field of "fast-fashion" powerhouses such as H&M and Zara. You might be thinking, "How did this NOT seem like a problem?!" However, as long as the money was rolling in, shareholders were happy and companies felt little incentive to buck the trend in strategy.

The problem really emerged when the frantic consumer spending cycles ground to a halt after years of proliferation, luxury labels slashed their prices, and core customers were left wondering what they were paying for in the first place.

Saving the Marriage

Just like any relationship on the rocks, luxury companies and their customers have to go back to their core values to re-build the bond that has been broken by years of inconsistency.

At the end of the day, a luxury company should represent solid quality and categorical leadership. The key words here are quality and leadership. When luxury brands diverge from their core capabilities where they exhibit the highest level of expertise, it is a letdown to all brand loyalists. When they chase the market instead of leading it, they let the brand down.

Many of the CEOs speaking at the Financial Times’ Business of Luxury Summit confirmed this attitude, including Berndt Hauptkorn, CEO if the privately held group Labelux. “During this period of growth, there were concepts that were superficial, that didn’t deliver in terms of product quality,” Hauptkorn said, arguing these brands won’t survive the economic downturn unscathed. “There will be a shakeout because there was overcapacity in the market. It will be a market with stronger brands and with a clearer message.”

Preserving Quality

The industry has begun to realize that once the economy recovers, customers will place a particular emphasis on values like quality and craftsmanship, but also exclusivity, as well as commitment to social and environmental responsibility. Companies that have remained true to their capabilities and core message throughout the boom years have seen less damage and a faster rebound than others in the recession.

In an effort to protect the intrinsic value of luxury brands, companies and production regions are going back to their most valued resources in production to strengthen intrinsic values in quality. According to Imran Amed, editor of Luxury Society, "In the end, it is the enduring quality and craftsmanship that count the most because this goes right to the heart of the way luxury products are conceived and created. Combined with great design, service and innovation, craftsmanship is what enables us to deliver lasting products that resonate with a new consumer mindset fixated on value."

While most luxury brands have cut back on retail space, collection sizes, and various departmental employees, for the luxury-savvy brands a focus remains on preserving the original craft of the brand. This includes the protection of craftsmen and artisans that produce their high-quality products, in addition to sustainable practices both environmental and strategic.

Having been through several recessions since he began creating the world's largest luxury group in 1985, Arnault stated that his key to success includes a solid long-term outlook: a generational business concept, not a 3-5 year plan. This allows a company to move forward with the big picture, and reduces the impulse to act on short-term trends in the market. “It is a natural tendency of companies during a crisis such as the one we are in to cut costs, drop prices, and stop expanding, because it has the most immediate impact on numbers,” he says. “But what we have learned in the many crises we have been through is that this is a mistake, especially when it comes to luxury."

Mr. Arnault also believes the government investment, reactive companies and a refusal to change course in spite of the current market crisis will help companies and production regions to preserve their capabilities. However, while some long-term-minded companies such as Chanel, Bulgari and Hermès have taken affirmative steps to preserve the dwindling numbers of craftsmen that produce their goods, other companies have stood by while production has been outsourced to unskilled worker regions abroad in the effort to feed the speeding consumer cycles of the boom years. While this labor pool of skilled workers is all but lost in the UK, there are efforts to retain and nurture growth there as well as in France and Italy.

Follow the Leader

In addition to increasing fashion cycles to pander to the whims of a fast-fashion-oriented market, luxury companies have been tailoring their products and marketing campaigns to lure existing customers.

The very history of luxury illustrates the point that luxury brands and designers provide items for the customer, which are so exciting the customer hadn't even thought of them. This is what originally made customers line up at the doors of the original artisans and designers- to see something new.

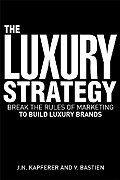

The recent years of endless market research, managerial consensus and client-centric focus on demand has diluted the interesting aspects of luxury. According to Jean-Noel Kapferer and Vincent Bastien, authors of Luxury Strategy – Break the Rules of Marketing to Build Luxury Brands, "Luxury brands today are the trailblazers of tomorrow’s taste. Once a consumer segment is identified it is too late to exploit it. ...There is no surprise in existing demand. This is why all classic luxury... was created through emotional intuition."

They go on to say, "As a cultural creator, luxury brands should set their own high standards. Listening to the consumer is the best route to a lack of differentiation, and failure to inspire the dream – the two levers of desire that are the only paths out of the recession in the luxury world."

While that does not mean companies should ignore the customer altogether (of course not), it does basically state the obvious that luxury players must be leaders in quality and innovation at all times, without submitting to frivolous market demands that might inflate the bottom line temporarily, but in the long run will break the bank and eventually the brand.

However, it should also go without saying that in order to be a leader, luxury brands must appeal to new consumers in Gen X & Y as Baby Boomers retire. In order to do that, they must earn their trust through demonstrated quality, sustainability and a legitimate brand story. And where will the new market hear that story? Online.

More Info

Financial Times' Business of Luxury Report 2009

http://www.ft.com/reports/business-luxury-2009

Luxury Society Issue 5: Return to the Craft

http://beta.luxurysociety.com/articles/a-return-to-craft

Luxury Execs Emphasize Exclusivity and New Focus

Luxury Execs Emphasize Exclusivity and New Focus - WWD.com

Shared via AddThis

The Latest on Ethical Fashion

The US government commits $60million to fighting exploitative child labor, but an all-out ban won't work.

Read MoreFashion History: The American System for Fashion

Paving the way for a NY Fashion District: American style, production and distribution align over American fashion

Beginnings

Menswear

The American clothing industry was born in the early 1800s for menswear. Up until this point, menswear was produced by tailors, for those whom could afford it, or at home as womenswear would continue to be produced for at least another half-century.

Around this time, tailoring businesses in the Northeast (NYC, Boston and Philly) began to produce and sell inexpensive ready-to-wear clothing to sailors on leave. These clothes were called slops, and were indicative of poverty or bad taste to the rest of society, but they provided a starting point from which the ready-to-wear market grew. The industry would further expand through the production of service and army uniforms.

In the early 1850s, a mass market of middle-class consumers emerged with industrialization. Brooks Brothers was among the first companies to serve this market, having begun in 1818 as a tailor-shop and growing to 75 tailors and 1,500 manufacturing employees by 1857.

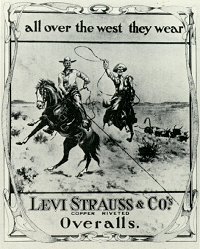

The mid-19th century "gold rush" had an even greater effect on the US fashion system. Mr. Levi-Strauss realized that the gold prospectors would need tents, and ordered a special resilient fabric from France to serve this market demand. The fabric was called serge de Nîmes (serge, from the French city Nîmes), which we now know as denim. In addition to using this fabric for tents, Levi-Strauss recognized that it could easily be transformed into utilitarian work trousers. American jeans were thereby born, and the development of the US fashion manufacturing system was well underway.

Alongside the invention of the sewing machine for industrial use by Isaac Singer, the US manufacturing industry was fully supplied with a growing immigrant labor force. However, the real key to success in this mixture was the alignment of distribution with production. Department stores and specialty stores began to focus more retail space and marketing efforts towards clothing. This alignment allowed the US fashion industry to move beyond workwear and menswear through superior production methods integrated with distribution, and a strong market orientation.

Even today, the US model for the fashion business is centered around vertical chains (meaning that they produce what they sell, like the GAP), department stores (although they are growing weak in the current economy), and a continued solid market orientation.

Womenswear

Many early-American women made their own clothes at home or locally, as thrift was a strong post-colonial value along with the patriotic challenge to the dominance of English/European taste. However, in the time of prosperity following the Civil War there was borne an interest in Parisian couture, and many American-made items were viewed as unsophisticated. While some could afford imports from France, most were American copies inspired by French fashion, yet they carried French labels to reassure their clientele (much like Italian labels are often used in the Chinese market today for Chinese-produced goods). The shadowing of Parisian style would continue well into the 1900s, the market demand of which fueled the growth of the American fashion industry.

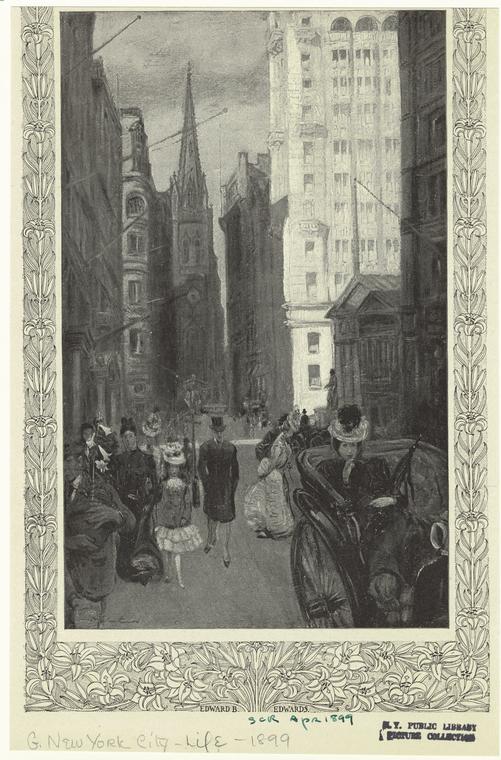

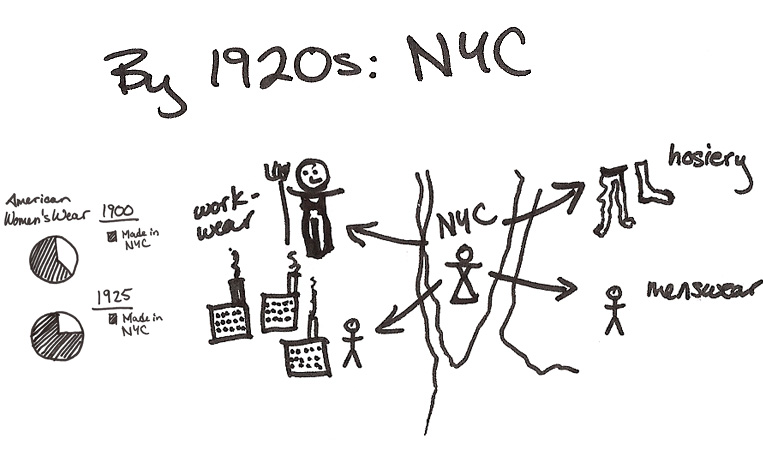

In the late 19th century, the concentration of transportation systems, manufacturing facilities, immigrant workers and skilled tailors in New York allowed for the rapid development of a concentrated fashion production region. In fact, New York had already become the capitol of ready-to-wear production by 1900, but by 1925, 78% of the fashion produced in Manhattan was in womenswear! The isolation of Europe from the United States during WW1 allowed for the American style to flourish. By the interwar years, the increasing trade of US ready-to-wear and growing consumer confidence in the "correctness" of the American way of life worked to solidify confidence in the American style.

WW2 went further to isolate the Parisian fashion capitol from the rest of the world, accelerating the idea of American sportswear and encouraging the isolationist attitude of the fashionable American woman, who increasingly viewed European fashion with suspicion rather than envy. By the mid-20th century, New York had become the fashion focus of the American woman, and the starkly functional and smart product style would remain the legacy of US fashion.

New York: Fashion Capitol, USA

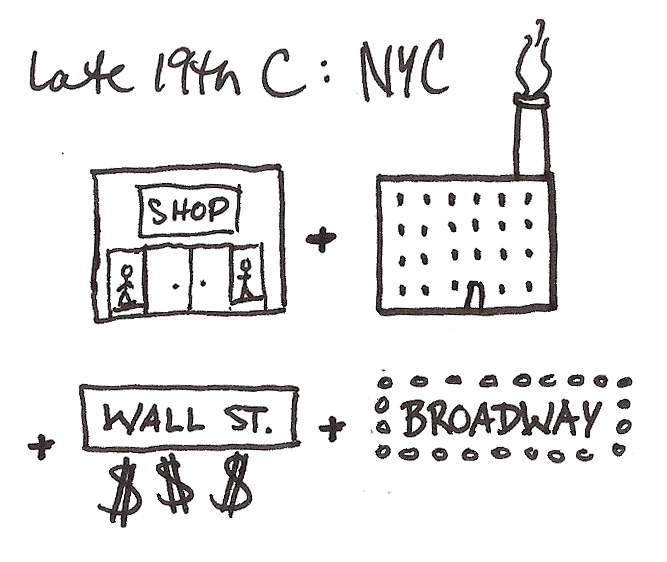

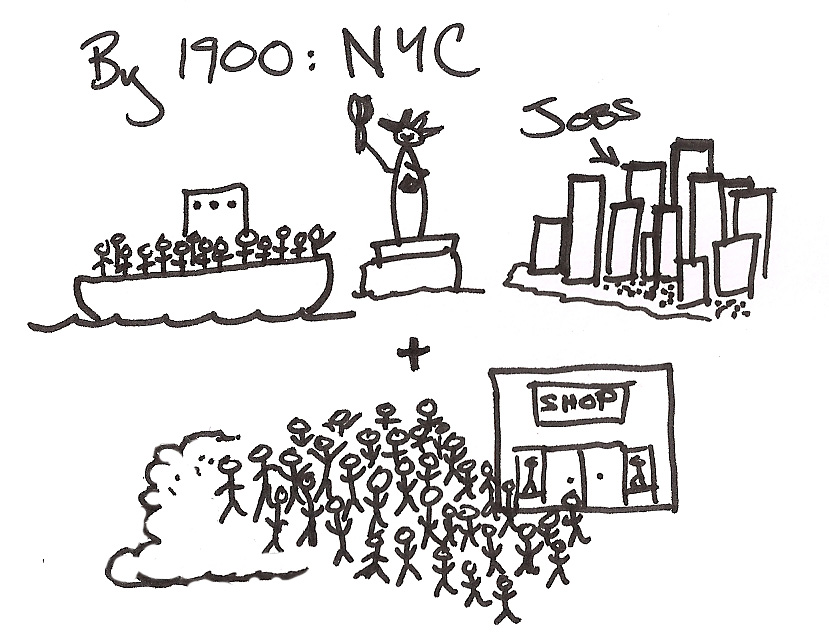

The story of the development of NYC into one of the world's leading fashion producers is pretty long and complex, so I've taken another tip from Dan Roam and sketched it out for the sake of brevity!

Paving the way for a NY Fashion District: pre-existing commercial and manufacturing facilities, along with fashionable aspirations and a less conservative attitude than other US cities.

Growing the NY ready-to-wear industry: huge immigrant labor pool & commercial demand

Regional growth & womenswear localization: centralizing women's fashion, outsourcing other production to suburbs

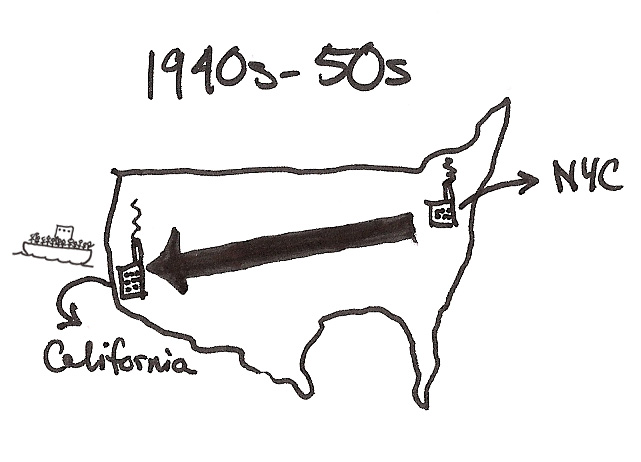

Challenging the leader: a second production region emerges around Hollywood, fueled by the film industry and a new wave of Eastern immigrants

Challenging domestic production: companies begin widespread outsourcing of production to Taiwan and the Pacific

Why New York?

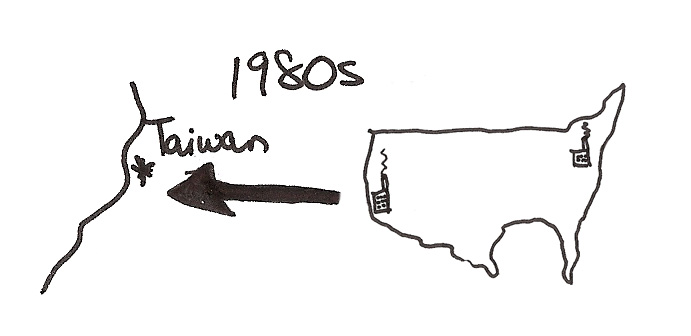

In spite of the 200+ years of clothing production evolution in the US, and several challenges posed by outsourcing for cheaper labor supplies, New York has remained the fashion capitol. How did it come to assume this position? Much like the fashion regions that would later develop around production in Italy, within New York an entire community of design, production, distribution, commerce and marketing existed (and much of it exists today). There are several groups that contributed to this phenomenon, among them:

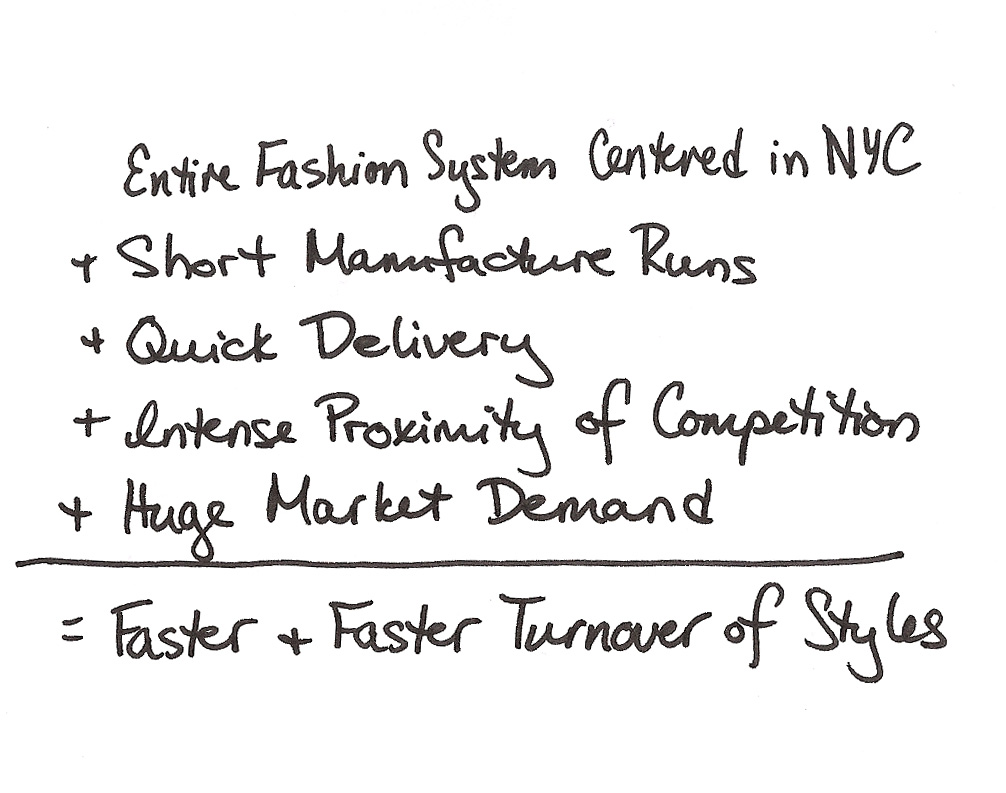

While the sweatshops have luckily vanished from New York, they still remain the curse of the ready-to-wear industry, having simply been moved to developing countries. In fact, the compact total-system for fashion that is found in New York has led to the global trend in "fast fashion," which demands cheap labor for rapid production and affordable prices. Put simply:

However, as "fast fashion" begins to slow down after years of increasing velocity (because, frankly, we are all getting sick of having our clothing be made obsolete as soon as we bring it home- where's the real value?), consumers are seeking more ethical alternatives to sweatshop-produced goods.

As New York has been at the heart of this movement and has led the way in both fashion marketing and production systems (whether domestic or outsourced), it seems likely that the movement towards ethical fashion will be centered from the market-driven capitol of NYC.

American Fashion Values

These same "values" and themes remain common to the American fashion system:

- Comfortability/Casual

- Sportswear & Jeans

- Practicality/Utility

- Sophisticated-Preppy

- Value for Money

- Clean Lines/Ethnically Neutral

- Apply Glamor to Basics

- Use Sport Motifs for Marketing

UPDATE!

Here is an incredible multimedia glimpse at the history of 20th Century American Fashion History from FIT.

Sources include: personal notes,Fashion, by Christopher Breward & Strategic Management in the Fashion Companies, by S. Saviolo & S. Testa