To compete within the luxury market, a product must have a balance between material, immaterial and distance characteristics. However, all points are subjective. In the end, there is no universal luxury product.

The Immaterial: Notoriety or Status

It is obvious that the term ‘luxury‘ implies a high level of quality, which we also understand is subjective. However, most of the value that sets one brand apart from another, in terms of luxury, is immaterial. That is, to say the symbolic properties that are related to identity, whether through self-identity or through status and group-membership. Fashion itself is centered around this concept: beyond clothing ourselves for protection, what we wear is on some level an indication of who we are or who we aspire to be.

Immaterial values are dependent on the cultural perceptions of luxury in each market. For example, the display of ostentation fluctuates between show-off and understatement, and what is considered to be modest in Miami is different from what is viewed as modest in, say, Vienna. An icon of the show-off class is Paris Hilton, especially in her pre-jail days. Note her shift to represent herself in a more understated way once she faced sentencing: she wanted to demonstrate to the world (and, more likely, the judge) that she had suddenly become more respectable, responsible, and less wild... and that she was willing to "tone it down". However, when you're opening a nightclub called “Vanity“ (and Paris is doing just that), it is pretty clear that ostentation and a show-off attitude are part of your identity (or brand, as it were). Contrast that with the late yet infamous Carolyn Bessette Kennedy, who is still known for her classic, understated elegance. She will likely remain a timeless icon of good taste and class, as her parred down and chic look seem less dated, more refined. Consider the difference in the communication of identity between these two:

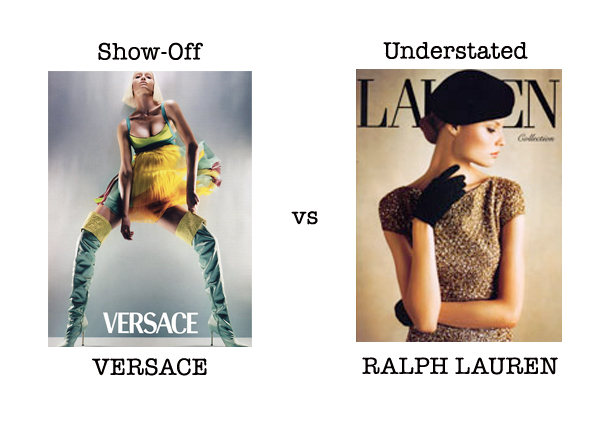

The same point can be made for brand identity. Whether in furniture or fashion, architecture or art, each brand or designer has a core identity that fits somewhere between the show-off and understated categories. For example, Versace has built a brand image based on the va-va-voom Botticelli Babe, South Beach, the supermodel society, and bleach, bleach, bleach. Contrast that with Armani's roots in minimalism, androgyny, clean lines and a subtly striking silhouette, or with Ralph Lauren's foundation in American Classic and aristocratic elegance.

Of course, even within one brand there are varying degrees of ostentation, and this is typically presented by way of line diffusion. In order to appeal to different market segments within the broader "luxury market," a brand will often produce a top-level line (haute couture or designer, for example) and then one or more diffusion lines that target a lower price point.

As you move further down a brand's diffusion into these lower price points, logos become increasingly important as quality and innovative design diminish. Armani can produce a basic white t-shirt that looks just like a Hanes, but if they stamp a massive logo across it, a consumer can still feel that they are buying into a piece of the Giorgio Armani lifestyle. That's the idea, anyway.

However, not all brands take this approach. A particular characteristic of French luxury brands is that they are often built around an elegant and iconic figure such as Coco Chanel or Dior's New Look lady, rather than a lifestyle, and these brands often avoid diffusion lines. For this reason, a brand like Chanel is able to offer both understated and show-off looks within the same line, though typically in separate stores, with less variation away from the core look, and always on the same pricing level.

Distance

The factor of distance often stands out as the definitive characteristic of the luxury product in the minds of many consumers. Rarity illuminates the notion of desire; it validates the idea that something is unique, special and somehow worthy of the term luxury. This is why companies like DeBeers take great measures to limit the number of diamonds on the market. More generally, this is also why limited editions are created: limited supply (plus great design, excellent quality and/or spectacular marketing) can create a frenzied sort of demand and support a premium price.

When considering the point of rarity or distance, you'll find that luxury brands go to extreme measures to exaggerate this point (as they well should). Aside from the obvious limited editions, distance is displayed (or hinted at) on every level.

In store merchandising, distance is conveyed by hanging only one or two units/sizes (SKUs) per product, instead of crowding the racks with every item in inventory. You must ask a sales representative for help, and he or she serves as a symbolic barrier between you and the product (any subtle intimidation there serves as an added psychological filter... you're welcome!).

In store displays, rarity comes across in carefully thought-out strategies. The Prada SoHo store displays merchandise like a museum with products arranged in still life settings or behind glass cases. Those Pierre Hermé cake shops in Paris are not designed like jewelry stores just to symbolize the quality of the products; it also communicates a sense of "Hands-off! Rare and precious items here! You can look, but you can't touch."

The Balancing Equation

A company could be said to be competing in the luxury market when they have a balance of three components: the material, the immaterial, and distance.

When one or two of these components are low, the other(s) must be high to compensate. For example, in lower level diffusion lines, where the quality (a material value) is similar to mass market products, the logo (or the immaterial) must be more prominent. If the material value of a Gucci key-chain is quite low, the immaterial value must compensate.

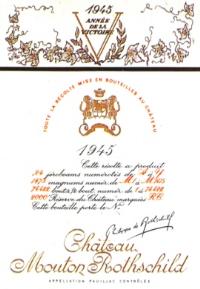

For a very rare and/or high-quality product, the immaterial value need not be so high. In 2006, a bidder at Christie's auction house broke the world record for the highest amount ever paid for a case of wine ($345,000 for a 6-bottle case of magnums). Unlike Gucci or Armani, Ferrari or Porsche, the brand of the wine was unknown to most non-connoisseurs. The wine was Château Mouton-Rothschild 1945. The background story is beautiful (man returns to his family vineyard in Bordeaux after WW2 and the Allied liberation to find his entire world destroyed, rebuilds and produces one of the most glorified wines of all time), the label is special and unique (marked with a V for victory after WW2, commissioned by a French artist and signed by the producer), and the quality of the wine is regarded by connoisseurs worldwide as remarkable.

Material: Is it a high quality wine? Many wine connoisseurs would argue that this Mouton is among the finest wines ever produced, however some would consider it merely good. Is it expensive? I certainly think so, but others might disagree.

Distance: Is it rare? Certainly: there were only so many bottles produced in 1945, so this is definitely a limited edition.

Immaterial: Does it convey status or identity? In some circles, yes; it is very famous. However, unlike many luxury brands that boast near universal fame, this Mouton is known only within more closed, expert circles. But, hey, if that's the group you want to be associated with, Château Mouton-Rothschild 1945 is certainly a hot entry ticket.

In the case of Château Mouton-Rothschild 1945, the material and immaterial properties are relatively subjective, however the rarity of the product is indisputable. Is it luxury? At $28,750 per bottle, and with a story like that, I would certainly consider it a luxury to experience this wine... however, I have been wine tasting in Bordeaux and would consider just about all of it to be luxury. To each their own.

(By the way, there is a great history of the Château Mouton-Rothschild estate and wines here.)

In the end, there really is no definitive luxury product, just a balance between these three points.