French fashion has long been reflective of social and economic hierarchy, illuminating the distinction among classes. Beginning with the Royal Court of the Sun King, France became the capitol of rich fashion. After Charles Worth created the business of haute couture in the 1800s, Paris became the creative center for a business model that has evolved greatly, yet still remains centered around the spirit of haute couture.

French fashion has long been reflective of social and economic hierarchy, illuminating the distinction among classes. Beginning with the Royal Court of the Sun King, France became the capitol of rich fashion. After Charles Worth created the business of haute couture in the 1800s, Paris became the creative center for a business model that has evolved greatly, yet still remains centered around the spirit of haute couture.

What is Couture?

Haute couture is identified as unique pieces constructed with precious materials, made-to-measure, and made for special occasions- not daily wear. A dress of this nature today should run you on average between 20,000 and 30,000 euro and up.

According to French law as of 2008, the following points must be met for a fashion company to be considered a house of couture:

- the atelier must produce at least 50 garments per season by hand

- the atelier must employ at least 20 skilled in-house workers for production

Note: This model is changing under the current economic situation, in order to protect the existing haute couture legacy; too many couturiers were closing their doors under the weight of these expensive restrictions.

Where there were once more than 30,000 clients per year for the highest form of French fashion, today there remain less than 3,000, and most of these are irregular clients. Hence, haute couture is not a big business anymore; it is unaffordable and impractical, as there are fewer and fewer occasions in today's world to wear such items. It has become much less profitable than it once was, having lost the link with modern life.

Most companies that made their name in haute couture today sell primarily accessible products and democratic accessories like lipstick, perfumes, and so on. However, to continue to sell these more "basic" goods at high profit margins, they must continue to produce high fashion. People are now buying the legacy of couture, rather than the couture itself. Therefore, to make the big bucks selling goods at the bottom, you must be positioned at the top.French companies based around haute couture lack a bottom-up business model, and have no second-lines: consider French powerhouses Dior and Chanel, as opposed to Armani, Ralph Lauren, Dolce & Gabbana, etc.

Most companies that made their name in haute couture today sell primarily accessible products and democratic accessories like lipstick, perfumes, and so on. However, to continue to sell these more "basic" goods at high profit margins, they must continue to produce high fashion. People are now buying the legacy of couture, rather than the couture itself. Therefore, to make the big bucks selling goods at the bottom, you must be positioned at the top.French companies based around haute couture lack a bottom-up business model, and have no second-lines: consider French powerhouses Dior and Chanel, as opposed to Armani, Ralph Lauren, Dolce & Gabbana, etc.

The Dream created by the haute couture collection is used to sell cheaper products from the same brand.

Brand images and communications demonstrate a high level of arrogance and provocation, in order to build The Dream. Have you ever wondered how or why that "crazy stuff that nobody is ever going to buy" makes it onto the catwalk? The most elaborate and provocative designs are taken onto the runway because the goal is not to sell as many units as possible, but to demonstrate creativity and uniqueness, and generate buzz around the brand. Consider the wild boys Jean Paul Gaultier for Hermes, or John Galliano for Dior (below).

Brand images and communications demonstrate a high level of arrogance and provocation, in order to build The Dream. Have you ever wondered how or why that "crazy stuff that nobody is ever going to buy" makes it onto the catwalk? The most elaborate and provocative designs are taken onto the runway because the goal is not to sell as many units as possible, but to demonstrate creativity and uniqueness, and generate buzz around the brand. Consider the wild boys Jean Paul Gaultier for Hermes, or John Galliano for Dior (below).

The buzz-factor has become increasingly important for luxury fashion labels in recent years, especially in France where the namesake designers (Dior, Chanel, Vionnet, Yves Saint Laurent, etc) are no longer with us. In fact, most clients are unaware of the designers behind today's major labels. Instead, it is much more common to know which celebrities are wearing which labels (the Poiret legacy lives on!).

The French Fashion System

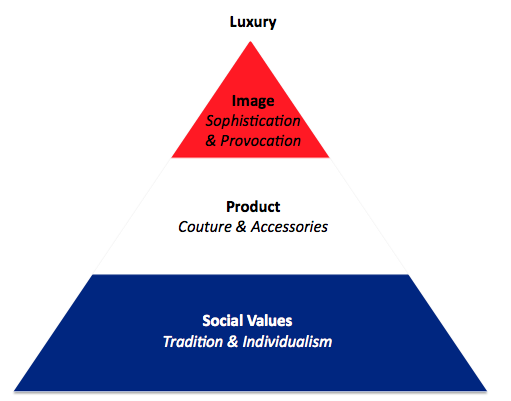

To summarize, the French business model is derived from a long tradition of craft and individualism... and marketing. Couture was the original product of the French fashion and luxury system, which was recently integrated with and then overtaken by accessories. The image of sophistication and provocation are used to produce the sense of luxury at the highest levels of the brand (through couture), which is what the companies are selling (through cosmetics and accessories). Viola!

- Couture = Image

- Accessories/Cosmetics = Sales

Here's my hastily-made visual (with apologies to France):

Prior to the mid-14th century, in Classical Periods, colors were dull and derived from a limited palette (typically white, yellow, red and some blues... all were dull). Clothing was neither cut nor sewn, but was draped indifferent to the body shape. Think: toga. Mid-14th century Europe brought about the appearance of a new type of clothing, with strong differentiation among men (short and tight, with silk tights) and women (long and close-fitting). Ah, how the times have changed!

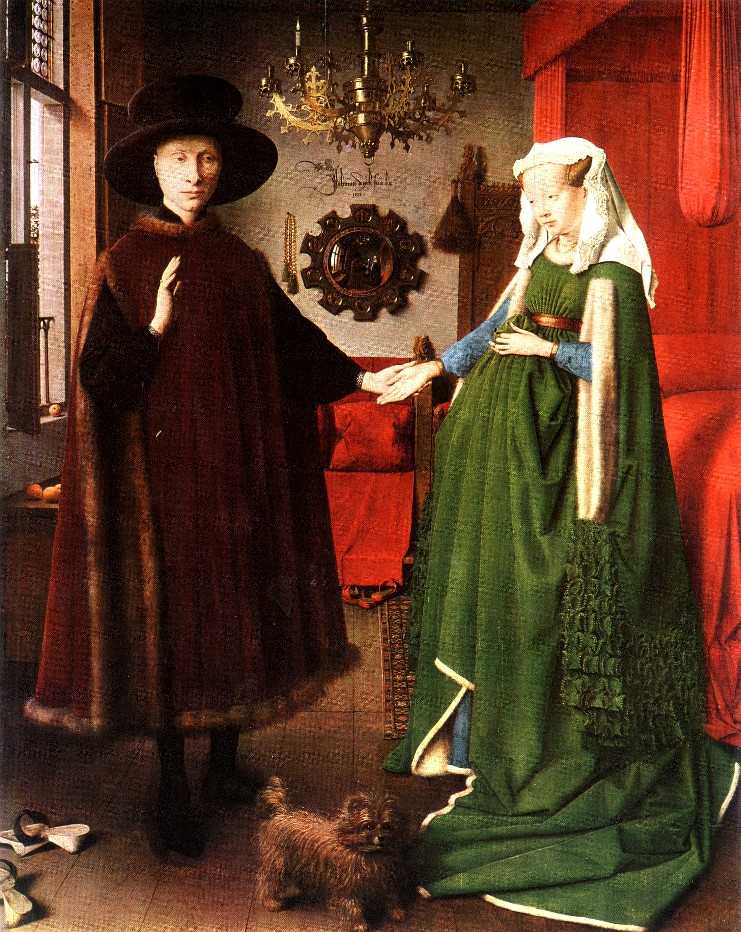

Prior to the mid-14th century, in Classical Periods, colors were dull and derived from a limited palette (typically white, yellow, red and some blues... all were dull). Clothing was neither cut nor sewn, but was draped indifferent to the body shape. Think: toga. Mid-14th century Europe brought about the appearance of a new type of clothing, with strong differentiation among men (short and tight, with silk tights) and women (long and close-fitting). Ah, how the times have changed! Colorful clothes were made possible due to improvements in dying. People in the Middle Ages placed great importance on color. The contrast in light versus dark, the social value of colors in the church or politics, and combinations of patterns or stripes prevailed. Take, for example, the famous Van Eyck painting, The Arnolfini Marriage, 1434. The husband is darkly dressed, demonstrating his seriousness, and that he is thrifty and committed. His wife wears green, demonstrating loyalty to her husband and wealth, while the white accents symbolize her purity. It was extremely difficult to find black or green clothing in this era, so this family is shown to be extremely wealthy.

Colorful clothes were made possible due to improvements in dying. People in the Middle Ages placed great importance on color. The contrast in light versus dark, the social value of colors in the church or politics, and combinations of patterns or stripes prevailed. Take, for example, the famous Van Eyck painting, The Arnolfini Marriage, 1434. The husband is darkly dressed, demonstrating his seriousness, and that he is thrifty and committed. His wife wears green, demonstrating loyalty to her husband and wealth, while the white accents symbolize her purity. It was extremely difficult to find black or green clothing in this era, so this family is shown to be extremely wealthy. Modern age trend setters were focused solely in the royal courts of Europe. The Spanish Court was known as the Black Triumphant. The Papal court also demonstrated magnificent elegance. Yet most important was the French court under Louis XIV. Versailles became the center os creation and diffusion of fashion, and Lyons became the center of silk production. The daily-changing spectacle that ended in revolution continues to influence fashion and culture through the tales of Marie Antoinette to this day. At the time, fashion ideas were transmitted through portraits, individuals (ambassadors or princes), gifts, and second-hand-clothes (the first example of ready-to-wear). We can see in this portrait of Louis XIV, he was quite a fashionable guy, with his wig, fur mantle, draped garment, silk stockings, and red heels!

Modern age trend setters were focused solely in the royal courts of Europe. The Spanish Court was known as the Black Triumphant. The Papal court also demonstrated magnificent elegance. Yet most important was the French court under Louis XIV. Versailles became the center os creation and diffusion of fashion, and Lyons became the center of silk production. The daily-changing spectacle that ended in revolution continues to influence fashion and culture through the tales of Marie Antoinette to this day. At the time, fashion ideas were transmitted through portraits, individuals (ambassadors or princes), gifts, and second-hand-clothes (the first example of ready-to-wear). We can see in this portrait of Louis XIV, he was quite a fashionable guy, with his wig, fur mantle, draped garment, silk stockings, and red heels!